Complex, but Clean: How Financial Technologies Should Be Developed to Promote Ethical Artificial Intelligence Systems

Dystopic scenarios where human jobs are performed by intelligent machines are not a novelty – they have been around since the 1920s, when Karel Čapek introduced the topic in his sci-fi novel, as well as the term robot.1 However, what may be more surprising is the fact that AI is currently having a greater impact, not in manual labor but analytical-thinking fields, such as white-collar professions: as businesses increasingly employ data-driven decision making powered by automated tools, the need for an extensive human analytic and management infrastructure shrinks along with the number of analyst job positions.2

The rapid growth of this disruptive business calls for scholarly analysis, to understand how it may affect the financial sector, and to figure out if it could be implemented in a way that maximizes the benefits of AI technology – such as time-saving, accurate risk assessments, organizational development, and client relations improvement, etc.3 – and minimizes the harms such as discriminatory bias.

More specifically, AI is being used by financial institutions for financial decision-making, as in credit referencing and fraud detection processes.4 A 2018 UC Berkeley study shows that fintech algorithms charge minority borrowers 40% less on average than face-to-face lenders.5 This is associated with the growing use of financial technologies such as automated trading which, according to the IMF corresponds to two-thirds of cash equity trading,6 generating implications for equal access to credit and socioeconomic development.7

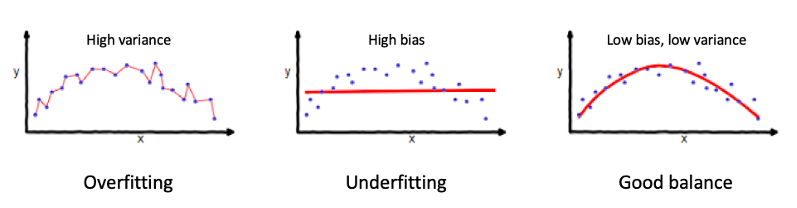

Two important ways to verify the adequacy of a model are by verifying its bias and variance. In the AI field, bias is the difference between the average prediction of the model and the correct value that it’s trying to predict.8 This term should not be confused with unfairness, which happens when AI bias causes discriminatory effects in society. If the bias is too high, it is said that the model is underfitting. Usually, refining the model by using the training and validation datasets is enough to adjust underfitting issues. However, it is important to bear in mind that the learning process requires biasing (especially when it comes to financial data), and no generalization can be done without some bias.9

The opposite problem is that of high variance, when the difference between the training and testing datasets is too high, which is called overfitting. When the model is overfitting, it may detect patterns in the training set which are not present in the general dataset.10 To better illustrate the difference between underfitting and overfitting, refer to the Figure above.11 Unfortunately, there is a trade-off between bias and variance, and both cannot be simultaneously avoided.12 There are many methods for finding the right balance such as regularization, boosting, and bagging, although they will not be presented here. However, beware that tuning the model by choosing appropriate datasets and algorithms is fundamental to avoid unfair discrimination when the model is used in social contexts.

Due to AI systems’ architecture, these algorithms become black boxes which make very challenging to assess why a particular result has been achieved, bringing opacity to the decision making process: it’s often unclear to determine the reasoning for a particular outcome (or output, in the IT vocabulary).13 Although this might be true due to how machine learning techniques operate (by learning from data instead of following a very structured framework), as it will be discussed later on, there might be some approaches that can help to identify and understand the reasoning behind an automated decision.

Sometimes, the fear of AI systems going beyond control has made some jurisdictions restrict/ban its use in judicial decision-making contexts. In France, there is a total prohibition of semi or fully automated decisions if such processing is intended to evaluate aspects of personality.14 Hungarian and Austrian law also seems to follow a restrictive approach, although less extreme than that of France.15 However, prohibiting the use of technological tools is rarely the best solution, since they usually have a strong disruptive characteristic due to their fast and wide adoption by society in many contexts. In this way, studying and trying to understand the phenomenon seems to be wiser than just avoiding the problem it causes and curtailing the development of new financial technologies.

To ensure the protection of citizens’ fundamental rights, it is necessary to answer the questions of who should be held responsible for errors in automated decision systems, and how this should be done. Therefore, accountability should be assigned to human elements present in the software decision-making cycle. Second, fairness should be guaranteed, and even though bias is an intrinsic factor of a machine learning system, it should never be set in a way that individuals’ rights and freedoms are significantly affected. Third, transparency should be in place to guarantee that the other two principles are implemented. These elements have also been highlighted in a study that mapped the global convergence towards five ethical principles which should govern AI systems design.16

Both the input data and the algorithm implemented are factors that influence the patterns and predictions created by the system. If there is no oversight of the dataset used as well as the parameters which are being set, there is a risk that these systems might reflect prejudices and discrimination already present in our society (as in cases of access to credit through outdated credit score systems).17 Therefore, financial institutions may take their part in promoting fairness in AI systems to better understand the reasoning behind an AI performance, explanations for why certain classifications are made should be given by the model.18

For the IT sector in financial institutions, methods are being developed to force statistical parity,19 which may reflect the idea of affirmative action policies (promoting equity instead of equality). The idea of giving preferential treatment to vulnerable groups in an attempt to “balance the odds” is implementable since bias is a characteristic of every AI system and can never (nor should) be truly eliminated. Fairness must be determined contextually and often must be reviewed ex-post.20

Another important step is testing the dataset (i.e. the system input) in the broadest possible way, as an attempt to mitigate the occurrence of unexpected outcomes due to new data. These may be implemented by the use of pseudorandom seeds that attempt to choose inputs as randomly as possible.21 However, it is also important to bear in mind that no matter how wide and random the testing is, it will never be fully able to preview all of the possible combinations that may result in a certain outcome (especially in unsupervised systems). Therefore, even after release, a machine learning system should be periodically reassessed to verify its consistency and to identify why certain undesirable outcomes are (i.e. unfair bias) happening.

Footnotes

[1] Thomas Ort, ‘Art and Life in Modernist Prague’ (2013) Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan (1st ed.) 23-55.

[2] Martin Ford, ‘The Rise of The Robots: Technology And The Threat Of A Jobless Future’ (2015) Oneworld Publications 94-95.

[3] Avaneesh Marwaha, ‘Seven Benefits of Artificial Intelligence for Law Firms’ (Law Technology Today, 13 July 2017) https://www.lawtechnologytoday.org/2017/07/seven-benefits-artificial-intelligence-law-firms/ accessed 3 April 2021.

[4] Ruairi O’Donnellan, ‘Racist Robots? How AI Bias May Put Financial Firms at Risk’ (Intuition, 24 February 2020) https://www.intuition.com/disruption-in-financial-services-racist-robots-how-ai-bias-may-put-financial-firms-at-risk/ accessed 24 March 2021.

[5] Robert Bartlett, et al., ‘Consumer-Lending Discrimination in the FinTech Era’ (2019) National Bureau of Economic Research 16 http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/morse/research/papers/discrim.pdf accessed 21 March 2021.

[6] IMF, ‘Global Financial Stability Report: Vulnerabilities in a Maturing Credit Cycle’ (2019) International Monetary Fund Publications Services https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019#ch1https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2019/03/27/Global-Financial-Stability-Report-April-2019#ch1

[7] Sian Townson, ‘AI Can Make Bank Loans more Fair’ (Harvard Business Review, 06 November 2020) https://hbr.org/2020/11/ai-can-make-bank-loans-more-fair accessed 24 March 2021.

[8] Alex Smola and S.V.N. Vishwanathan, ‘Introduction to Machine Learning’ (2010) Cambridge University Press (2nd ed.) 69.

[9] Nils J. Nilsson, ‘Introduction to Machine Learning’ (2005) Stanford University Press (1st ed.) 9.

[10] Ibid., 81.

[11] Seema Singh, ‘Understanding the Bias-Variance Tradeoff’ (Medium, 21 May 2018) https://towardsdatascience.com/understanding-the-bias-variance-tradeoff-165e6942b229 accessed 12 March 2021.

[12] Stuart Geman, et al., ‘Neural Networks and The Bias/Variance Dilemma’ (1992) Neural Computation 4 1-58.

[13] Emre Bayamlioglu, ‘Contesting Automated Decisions: A View of Transparency Implications’ (2018) European Data Protection Law Review 4 445.

[14] Gianclaudio Malgieri, ‘Automated Decision-Making in The EU Member States: The Right to Explanation And Other “Suitable Safeguards” In The National Legislations’ (2019) Computer Law & Security Review 35 20.

[15] Ibid., 26.

[16] The two other principles are non-maleficence and privacy. See Anna Jobin, et al., ‘The Global Landscape of AI Ethics Guidelines’ (2019) Nature Machine Intelligence 1 389-399.

[17] Judith Hurwitz and Daniel Kirsch, ‘Machine Learning for Dummies’ (2018) John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 20.

[18] Joshua A. Kroll, et al., ‘Accountable Algorithms’ (2016) University of Pennsylvania Law Review 165 48.

[19] Yukun Zhang and Longsheng Zhou, ‘Fairness Assessment for Artificial Intelligence in Financial Industry’ (2019) 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 5 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337966581_Fairness_Assessment_for_Artificial_Intelligence_in_Financial_Industry accessed 13 March 2021.

[20] Joshua A. Kroll, et al., supra note 18, 51.

[21] Ibid., 34.